It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that, in recent years, some of the most fascinating and substantial Farsi-language content has come from Dr. Azarakhsh Mokri — a psychiatrist, associate professor at Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and the educational deputy at the National Center for Addiction Studies.

I first encountered Mokri’s lectures about three years ago; back then, it seemed that his audience mainly consisted of psychologists and students in related fields. However, it didn’t take long before his reach expanded, attracting a broader and more diverse group of listeners.

Just take a look at the way Mokri’s talks have been received on social media. You’ll notice that, especially in the past couple of years, his audience is no longer limited to psychologists or graduates of natural sciences.

Why Is Public Attention to Mokri’s Work a Positive Sign?

One of the well-founded criticisms of the scientific community has been its inability to effectively communicate science to the general public. Consider the title of an article by Paul M. Sutter, an astrophysicist:

Science faces two major challenges: communicating ideas and building human connection. People need to see scientists not just as information sources but as real, relatable individuals. Yet, significant barriers stand in the way of such connection.

The article is intriguing, but frankly, it must be said: until the rise of scientific podcasts, delivering scientific content to non-specialists was often viewed by parts of the academic world as something beneath the dignity of academia. Some believe that the wave of anti-science sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic confirmed this — showing how the scientific community struggled to establish human, social, and trustworthy communication with the broader public. Even so, social media and the web have created a tremendous opportunity for specialized knowledge to reach the public.

In my view, figures like Andrew Huberman (who certainly deserves a dedicated post himself) and, within the Farsi-speaking world, Azarakhsh Mokri, represent successful examples of science communication. The more accessible and engaging real scientists and critical thinkers become, the harder it will be for pseudoscience promoters, charlatans, and opportunists to dominate the public space.

Where to Find Azarakhsh Mokri’s Content

Bless the person who set it up—Mokri’s website, mokri.org, serves as a hub for organizing, archiving, and sharing his lectures and public content. In addition, Mokri maintains active social media channels:

- Instagram: @azarakhshmokri

- Telegram: DrAzarakhshMokri

- YouTube: @DrAzarakhshMokriOfficial

In my opinion, one of the most engaging aspects of Dr. Mokri’s work is his presentation and curation of important books by some of the world’s most influential thinkers.

All of us are, by necessity, bound to prioritize deep study within our own fields of expertise. As a result, we often lack the time or energy to meaningfully explore other domains—and we might even go through life unaware of astounding discoveries made outside our intellectual bubble. On the other hand, without sufficient background or guidance, wandering solo into unfamiliar disciplines can easily lead to misinterpretation or superficial understanding of complex material.

By selecting and explaining key works in fields such as social psychology, behavioral sciences, and—occasionally—cognitive science (domains whose insights are valuable and arguably essential for any curious mind), Mokri has managed to deliver high-quality, accurate content to non-specialist audiences—without resorting to over-simplification, sacrificing scientific precision, or diluting the message with excessive personal opinion.

A Habit of Critical Thinking: Critiquing Mokri

I’ve made it a personal rule that whenever I become particularly drawn to someone’s ideas or persona, I should apply even more scrutiny than usual—otherwise, interest can too easily slide into blind reverence. So it’s only fair that I raise a few critiques about Dr. Mokri’s work.

Although the ideas he presents are drawn from some of the most robust intellectual traditions globally, one major element feels somewhat underrepresented: geography. Much of the research he references relates to the habits and challenges of people in developed nations—societies with drastically different economic, social, and cultural conditions. Iranian society, with its layers of political, economic, and social crises, faces far more severe realities. It’s a bit like spending most of your time talking about the flu when cancer is already on the horizon. That said, I do agree that just because we’re grappling with cancer doesn’t mean we should ignore the flu and fall behind the rest of the world.

To be honest, I realize this expectation may be unfair. When I decided to launch this blog, I hesitated for a month, carefully drafting a checklist of self-censorship rules and designing a low-risk strategy—just to feel relatively safe and avoid unnecessary scrutiny. I’ve even created an impressive internal system of cognitive distortions and rationalizations to keep myself from falling into cognitive dissonance! So how can I expect prominent researchers, with public and academic visibility, to speak with complete openness or directly attack the “cancer cells”? Maybe instead of demanding more from them, I should be a supportive audience—one that helps make the road smoother for those trying to bring science to the public without unnecessary baggage.

With that, let’s begin introducing Dr. Mokri’s discussions on free will.

Talks on Free Will

As someone who is not an expert in cognitive science, philosophy, or behavioral sciences, I found Dr. Mokri’s exploration of free will to be one of his most compelling topics. As far as I’ve been able to follow, the books discussed in this lecture series include:

- Neuroexistentialism – edited by Gregg D. Caruso and Owen Flanagan

- Restorative Free Will: Back to the Biological Base – Bruce N. Waller

- Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will – Robert Sapolsky

(This last book has also been translated into Persian.)

There was also a reference to Four Views on Free Will by John Martin Fischer and others, as well as Free Agents: How Evolution Gave Us Free Will by Kevin J. Mitchell.

The talk on Free Agents was never delivered, and in my opinion, ending the series with Sapolsky’s deterministic framework left the overall discussion feeling incomplete.

Why the Free Will Debate Matters

We often intuitively feel that we aren’t entirely in control of our decisions or behaviors. Most of us can recall moments when we thought we had “no choice” or felt something was “not really our fault.” For instance, we may initially feel disgust or demand punishment toward a criminal—only for that reaction to soften into empathy after learning about their childhood or past traumas. These kinds of experiences push us to ask deeper questions about responsibility, agency, and justice. Below are some foundational questions that lie at the intersection of modern scientific fields—from biology and psychology to neuroscience and physics:

Core questions:

- If modern science and empirical methods tell me that my personality is a product of genetics, environment, education, and past experiences, can I truly be held blameworthy for my negative actions?

- In other words, if “I” am merely the outcome of processes outside my conscious control, what does personal responsibility even mean?

- If my good behavior also stems from biological or emotional predispositions—say, I don’t do harm simply because I’m wired in a way that prevents me from doing so, and I feel discomfort when I do wrong—are such good actions still worthy of praise? Can I honestly see myself as “morally superior” to someone who, in similar circumstances, makes a harmful choice?

- Findings from neuroscience prompt us to wonder whether the feeling of “choosing” is actually an illusion manufactured by the brain (see Libet’s experiments). If that’s the case, are our decisions truly made by our will—or are they just reflections of actions already underway?

- If the universe operates under strict causal laws and everything is the result of prior causes (i.e., is “deterministic”), can free will even exist within that framework? And if quantum physics—via the principle of indeterminacy—allows causality to be broken, is what replaces it just randomness? Or could it make room for a new kind of genuine freedom?

I don’t intend to summarize the entire debate here, but I will offer a few key definitions to make it easier to follow the upcoming discussion. These definitions may help organize the topic and clarify how its core concepts connect. Please note that I have compiled these definitions myself; therefore, if an expert finds fault with any of them, it should be understood that they are not drawn from Dr. Mokri or the authors of the aforementioned texts.

Determinism and Indeterminism

One of the central pillars in the discussion of free will is determinism. If we aim to explore the topic of free will without first grasping determinism, we’ll quickly run into conceptual roadblocks.

Determinism means that every event necessarily occurs in the only way it possibly could—due to prior causes, previous conditions, and the governing laws of the universe. In a deterministic world, the present and the past (if fully known) are sufficient to predict the future with precision. The term has sometimes been translated as “necessity” or “fate,” but this is misleading, as it carries connotations of fatalism which differ from philosophical determinism.

Determinism has several interpretations across various fields, but within the debate on free will, three primary forms are especially relevant:

-

Biological Determinism: Based on neurological, genetic, and hormonal structures that influence our actions and decision-making.

-

Socio-Cultural Determinism: Emphasizes the role of institutions, language, upbringing, social class, and culture in shaping individual choices.

-

Probabilistic (Statistical) Determinism: This view relies on probabilistic rather than certain predictions. In some areas of physics—particularly quantum mechanics—absolute determinism is replaced with statistical models.

The translation of determined as ta’yin-shodeh (تعیینشده) by Mokri was a clever choice; it lightens the heavy burden of abstract philosophical terminology and makes the concept more accessible to readers unfamiliar with philosophy.

Indeterminism, in contrast, refers to a condition in which events are not entirely predictable, even if complete initial information were available.

In such a state, indeterminate or random factors come into play. In fact, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle—which will be explained next—challenges the classical definition of determinism.

Causality and Its Relationship with Determinism (Causal Determinism)

Causality refers to a relationship in which one phenomenon (the cause) brings about another phenomenon (the effect).

Causal Determinism means that every phenomenon is entirely governed by its prior causes—i.e., all events inevitably and without exception result from preceding causes, and nothing occurs spontaneously or randomly.

However, causal determinism doesn’t align neatly with the findings of modern physics, particularly quantum mechanics, where non-causal behaviors are observed at the level of fundamental particles.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty means that predicting or determining the future state of a system or event either isn’t possible in principle or is only possible probabilistically. This can result from a lack of information, the inherent complexity of the system, or even from the fundamental nature of reality itself.

In quantum physics, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle states that it is impossible to simultaneously measure both the position and momentum of a particle with perfect precision. This limit arises not from a shortcoming in our tools or knowledge, but from the very structure of physical reality. In this domain, classical causality—where phenomena are the result of a precise and linear chain of causes—no longer holds. Instead, the behavior of particles can only be described in terms of statistical distributions.

In other words, on the subatomic scale, fundamental particles like electrons or photons exist in a superposition of multiple possible states prior to measurement. Their status is not only indeterminate but intrinsically probabilistic and non-deterministic.

In classical probability systems, if all initial conditions (e.g., angle and force of a die throw, surface friction, etc.) are known, one could theoretically predict the outcome, even if doing so in practice is difficult. But in quantum mechanics, even with complete knowledge, definitive prediction is impossible—because at this scale, nature itself is governed by randomness. This fundamental difference presents one of the most serious challenges to traditional understandings of causality and, consequently, to the notion of strict determinism in physics. Nonetheless, appealing to randomness, from the perspective of determinists, does not help in establishing free will—because random events lie outside individual control, and are not a manifestation of freedom.

Free Will

Free will refers to the human ability to choose or decide freely, without external or internal constraints. In this concept, a person can make a choice from different options and take full responsibility for their actions. Free will is a significant topic in ethics and psychology, as it relates to issues such as personal responsibility, morality, and human decision-making. Moreover, in many religious and spiritual theories, free will is presented as a tool for testing and making moral choices.

Now that I’ve defined the basic concepts, let’s move on to the four categories of thinkers.

Categories of Free Will Thinkers

This categorization is based on three key questions:

- Do they view the world as based on determinism or indeterminism?

- Do they believe in free will?

- Do they consider free will compatible or incompatible with determinism?

Based on these, four distinct belief positions emerge:

| Belief in Determinism | Belief in Free Will | Category | Thinkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Yes | Compatibilists | Daniel Dennett, Manuel Vargas |

| Yes | No | Hard Determinists | Robert Sapolsky, Sam Harris |

| No | Yes | Scientific Libertarians | Robert Kane, Kevin J. Mitchell |

| No | No | Hard Incompatibilists | Derk Pereboom |

Agent

An agent is an entity or system that has the ability to process information, make decisions when faced with options, and take purposeful actions. An “agent” typically has some form of awareness of its environmental or internal state, the ability to choose based on that state, and the capability to make changes in the environment or itself.

This concept is defined differently across various fields:

- In philosophy of mind and ethics, an agent must possess a kind of self-awareness, intention, and moral responsibility.

- In neuroscience and cognitive psychology, agency is related to causal information processing, executive control, and the ability to plan.

- In artificial intelligence and complex systems theory, an agent can be non-human, artificial, or even non-biological, as long as it can act autonomously in interaction with the environment.

As a result, “agent” is a spectrum concept that, depending on its level of complexity, can include everything from rational human beings to self-governing, self-organizing artificial or biological systems.

Moral Responsibility

Moral responsibility refers to the ability to be held accountable for one’s actions, based on the premise that one could have made a different choice. This concept is centrally linked to free will and forms the basis for many legal, ethical, and social structures. It holds significant importance for the architects of future societies.

Personal Belief:

Nearly all four categories—whether those who firmly believe in the absence of free will or those who consider it partially existent—cannot deny the fact that, even if free will exists, the influence of personal will and choice on issues like crime and punishment is limited and even minimal. However, does the world, with its limited resources, have the capacity for rehabilitation, or should we continue to blind ourselves to the truth and convince ourselves that we are fair beings; that they deserved it?

Libet Experiments

The Libet experiments are among the most important in the history of neuroscience, demonstrating that brain activity initiating decision-making occurs before an individual consciously becomes aware of their decision. These experiments were first conducted by Benjamin Libet in the 1980s and later repeated in various forms using advanced technologies such as fMRI and more precise testing methods. The approach taken in these experiments is referred to as the “Libetian approach.”

This part is quite fascinating; I recommend you not miss it. For Persian speakers, Mokri addresses this both in his presentation of both books “restorative will” and “determined“.

Thank you for pointing that out! It seems I misunderstood the reference. You were referring to Mokri, not Machiavelli. Let me correct that.

The Behavioral Science Approach to Free Will Research

Although the Libet approach and its experiments have faced serious criticism, there is evidence in behavioral sciences and experimental psychology that will send shivers down your spine.

Various findings in modern neuroscience, from experiments on unconscious effects on decision-making to studies on environmental and social influences, indicate that our decisions, even when considered as “free will,” are deeply influenced by hidden factors. This approach shows us how, even if we have free will, our choices are heavily impacted by these hidden factors.

Mokri has some lectures titled Hidden Factors in Our Decisions. If you know Persian, you’re interested in this topic, I recommend listening to them first. I’m sure you’ll enjoy it.

The Evolutionary Approach to Free Will

A group of thinkers view free will as a biological and evolutionary trait that has emerged through the process of evolution. These thinkers point to several factors that strengthen the evolutionary value of free will.

One approach refers to the uncertainty and randomness inherent in biological processes at the cellular and molecular level. In fact, some argue that Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle provides a basis for the possibility of free will, as there is evidence in mechanisms at the single-cell level or at very small neural scales that support the idea of randomness. Although the majority of neuroscientists view the brain more in terms of classical mechanics rather than quantum mechanics, this idea still persists.

Another approach they take is observing unpredictable behaviors in animals; they view free will as arising from evolutionary processes within complex biological systems.

Complex Nonlinear Systems

These systems are ones where the outputs cannot be predicted in a simple or linear manner from the inputs. Such systems exhibit emergent behaviors, which are sometimes suggested as an alternative to the linear causality model in the study of free will.

Emergence

An emergent property or behavior arises at the macro level of a system and cannot be reduced to its individual components. Some theories consider free will as an emergent phenomenon arising from complex neural and social interactions. If you can’t accept that our conscious behavior is entirely deterministic, it might be a good idea to research this concept and its mechanisms further.

Final Thoughts

Free will is one of the fascinating topics that Dr. Azarakhsh Mokri has brought to our attention through his examination of prominent books. If you’re interested in the discussion, start with Restorative Free Will and make sure to listen to Determinism and Neuro-Existentialism as well.

Want my own conclusion on free will? Well, I conclude with my bitter but popular mantra: I don’t know.

Sure, here’s a more humorous and sarcastic take on the translation:

Anyway, every time we feel the urge to punish people for their actions and look at criminals with that “how could they?” expression, or when we start patting ourselves on the back for our superior moral virtues, or throw a grand celebration for our achievements, or, let’s not forget, when we feel the need to proudly boast about our “superior genes,” it might be a good idea to remind ourselves that, maybe, just maybe, getting ahead of bad luck isn’t as worthy of a parade as we think.

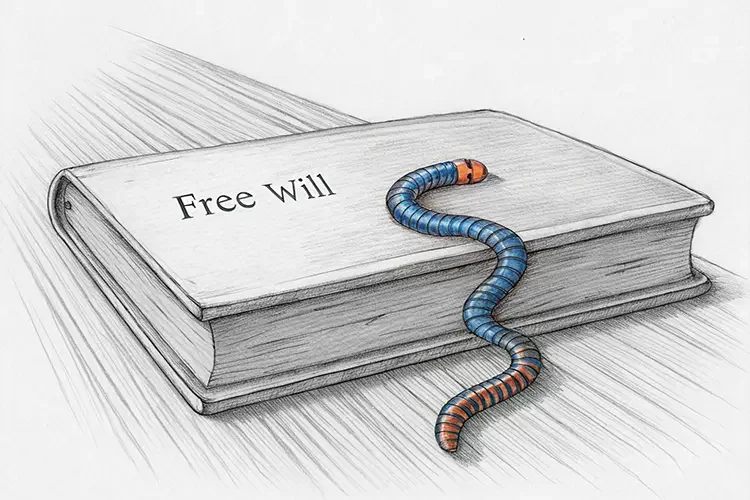

By the way… as I was cleaning up this conclusion, a worm popped into my mind… I started chatting with it. If you’re curious, you can read all about it in this reflection section.

The audio file of this article is Hungarian Dances: No. 19 by Brahms